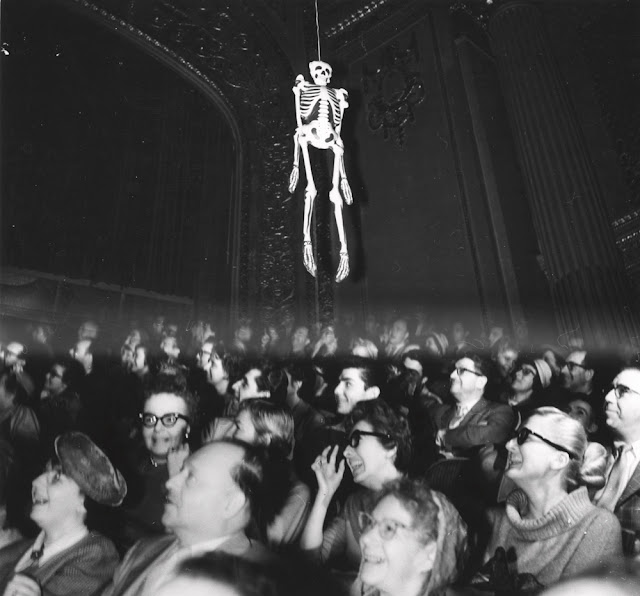

Imagine you’re sitting in a 1959 movie theater. You’ve paid your hard-earned 50 cents to watch “The House on Haunted Hill.” You’re ready for some good old-fashioned scares, courtesy of Vincent Price and his creepy mansion. The lights dim, the projector whirs, and the movie begins. Everything seems normal until, at a critical moment, a plastic skeleton comes floating above the audience. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Emergo, the most hilariously audacious gimmick in the history of horror cinema.

The Birth of a Gimmick Genius

William Castle, the P.T. Barnum of horror movies, was always one step ahead in the gimmick game. Before “The House on Haunted Hill,” Castle had already experimented with other outrageous ideas. He gave us insurance policies for death by fright and rigged theater seats with buzzers. But Emergo? Emergo was his magnum opus.

Castle’s idea was simple yet brilliant: during a crucial scene in the movie, a skeleton would seemingly emerge from the screen and float over the audience, creating an immersive and interactive horror experience. In Castle’s own words, he wanted to “reach out and touch” his audience. Or, more accurately, he wanted a plastic skeleton to do it.

Building the Skeleton

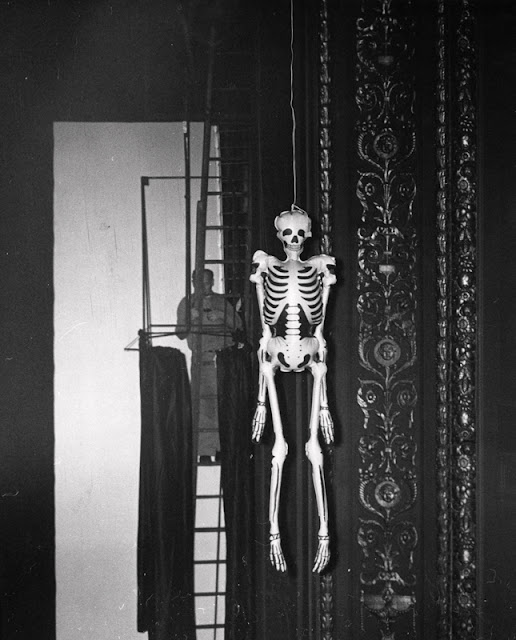

You might think constructing an airborne skeleton is easy. You’d be wrong. Castle didn’t just grab any old skeleton; he had to ensure it was visible in the dim theater light. The skeleton was affixed to a series of pulleys and wires, which allowed it to glide menacingly over the heads of the audience. This setup was not only mechanically impressive for its time but also required precise timing to synchronize with the movie’s pivotal moment.

However, the execution was far from flawless. Theaters were not built to accommodate Castle’s contraptions. Projectionists had to be trained on how to operate the skeleton, often leading to hilariously unintended consequences. There were reports of the skeleton getting stuck mid-air or crashing into the audience, which, let’s face it, only added to the fun.

The Audience Reacts

Imagine the scene: the movie is building suspense, Vincent Price is doing his thing, and suddenly, a skeleton floats above you. The reactions were mixed, to say the least. Some audience members screamed, others laughed, and a few probably wondered if their drink had been spiked. Castle’s gamble paid off in terms of sheer memorability. People left the theater with a story to tell, and for Castle, that was the real victory.

But not everyone was a fan. Critics were less than kind, calling the gimmick cheap and distracting. Castle, however, was unapologetic. He knew his audience, and he knew they came for an experience, not just a movie. In his mind, the more outlandish, the better.

Technical Difficulties

Emergo was not without its technical hiccups. As mentioned, the skeleton often got stuck or failed to deploy correctly. There were even instances where theater owners refused to implement the gimmick due to the additional labor and potential hazards. Castle had to deal with the logistics of installing and maintaining the rigging in each theater, a task that was as frustrating as it was essential to his vision.

One particularly famous incident involved the skeleton breaking free from its wires and falling into the audience. Instead of causing a panic, it turned into a comedy moment, with the audience tossing the skeleton around like a beach ball. Castle probably would have approved; after all, any reaction was better than no reaction.

The Legacy of Emergo

While Emergo might seem quaint or even laughable by today’s standards, its impact on the horror genre and movie marketing cannot be overstated. Castle’s use of Emergo demonstrated the power of immersive theater and interactive experiences long before they became a staple in theme parks and haunted houses. He understood that horror wasn’t just about what was on the screen but about creating a visceral, shared experience.

Modern horror owes a lot to Castle’s innovative spirit. His willingness to take risks and embrace the absurd paved the way for other gimmicks and interactive experiences. Today, we have 4D theaters, virtual reality horror experiences, and even immersive theater productions where the audience is part of the show. All of these owe a debt to the skeleton that floated over the heads of unsuspecting 1950s moviegoers.

Final Thoughts

William Castle’s Emergo was a stroke of marketing genius wrapped in a plastic skeleton. It was ridiculous, it was audacious, and it was pure Castle. In an era where horror was often confined to the screen, Castle dared to break the fourth wall and involve his audience in the madness. Sure, it didn’t always work perfectly, but that was part of the charm.

Emergo wasn’t just a gimmick; it was a statement. It said that horror could be fun, interactive, and above all, memorable. It invited the audience to be part of the scare, to laugh at the absurdity, and to enjoy the communal thrill of a shared experience. Castle understood that horror is as much about the buildup and the reaction as it is about the scare itself.

So next time you watch a horror movie, think about the plastic skeletons and the crazy ideas that paved the way for today’s immersive experiences. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll wish a skeleton would float over your head, even if just for a moment.

William Castle, we salute you. Emergo forever.